Incident Reporting

Reporting on an individual death in a timely manner is one easily-recognizable category, and the one for which most recommendations drawn up by non-journalists have been primarily designed. The dominant concern behind such “guidelines” in recent years has been contagion, in which studies have shown that certain types of incident reports handled in certain ways can be associated with other “copy-cat” suicides in the days or weeks following. As explored in the new chapter, this is a serious clinical concern whose effects journalists should seek to minimize in responsible coverage.

The majority of suicides occur without making the news, just as the vast majority of deaths from other causes do. The chapter discusses the elements of newsworthiness in some detail. Once the decision to cover has been made, the question is how to do so responsibly, given that the public benefit to be attained by reporting may appear to be relatively minor. But the cumulative effect is also relevant, as is discouraging the growth of harmful rumour through straightforward, factual and timely reporting.

In most cases where a suicide incident is reported as a news story, contagion reduction may be among the most significant factors reporters and editors need to consider. One must bear in mind, however, that it is just one of 14 factors researchers have identified as drivers of suicide rates, and it is by no means the most influential of them. (Source: New England Journal of Medicine, January 16, 2020 - Seena Fazel, M.D., and Bo Runeson, M.D., PhD.)

In the examples that follow we present some instances in which reporting a particular suicide death presented challenges for journalists. We consider, with the benefit of hindsight, how well the balance between public good and potential harm was handled. These three cases were studied for Mindset by Paul Benedetti, senior journalist, columnist, author and former program coordinator of the Master of Arts in Journalism at Western University.

Case study #1

Alberta Legislature Death

Monday, December 2, 2019, around 3 p.m., a man shot himself with a handgun on the steps of the Alberta Legislature in Edmonton. He died at the scene.

Even under the usual newsroom discretionary guidance for suicides, this incident merited being reported upon. It met several of the criteria for coverage: the death occurred in a (very) public place; it resulted in disruption of the proceedings of the provincial legislature; and it involved a large and public police response in the centre of a major city. These factors alone made the death news. Adding gunfire in the proximity of the legislature made it impossible to ignore.

Though most news outlets covered the incident with admirable restraint and adhered to most of Mindset’s best-practice recommendations – including not sensationalizing the death and providing information about mental health and suicide prevention services – there were some problems with the coverage.

Police information and early media reports were vague and confusing, at times suggesting the man may have gone to the legislature to commit a crime and/or that he was killed by security guards. Neither was the case. Initial reports stated that the legislature proceedings were interrupted “after a shooting on the front steps of the building” and after “an incident involving a firearm.” Stories that followed were much clearer using the words “suicide”, “non-criminal” and descriptive phrases such as “man dies by suicide” and “after a person died by suicide”. Clarity demanded that the usual practice of avoiding describing the precise means of suicide was suspended and all stories included that the man died of a self-inflicted gunshot. Almost all other details were omitted though several stories included a brief description of the victim’s clothes.

The stories, particularly those that followed a day or two later, pursued two questions that were salient:

“Who was this man?” and “Why did he take his own life on the steps of the legislature?” These questions put reporters squarely between two competing recommendations on suicide coverage. On the one hand, they were seeking to illuminate broader social issues; and on the other, trying to respect the privacy and grief of the family. The stories were, in general, responsible. On the positive side, readers learned that the victim, a military veteran, suffered from mental health problems - mainly depression – and that he had reached out to public officials about access to assisted death for mental suffering, all of which shed light on several important public issues. As well, almost every story provided information to readers on mental health resources and suicide prevention services. But, there were some complicating factors. Though reporters are cautioned about contacting family members immediately following a suicide, that was done in this case with willing family members. At least one story contravened a key Mindset recommendation to not “characterize [suicide] as a solution to problems”. The victim’s stepson framed the suicide somewhat positively noting that the deceased was now “pain free”, saying: “This man is not in pain anymore… that’s where he wanted to be.”

Reporters must balance the duty to report about an event in a public place that touches on public policy issues with an equal duty to strive to “avoid unnecessary harm.”

Mindset suggests caution with family-member input and recommends using quotes or clips from qualified people, such as psychologists, psychiatrists and other mental health experts.

Case study #2

The death of doctor working on the front lines of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Dr. Lorna M. Breen, the director of the emergency department at New York Presbyterian Allen Hospital in New York City, died by suicide Sunday, April 26, 2020 at her sister’s home in Charlottesville, Virginia. Dr. Breen had contracted COVID-19 while working with infected patients. After a week and a half off, she returned to work, but was unable to complete her shifts. A physician colleague suggested she go to her family’s home in Virginia to recover. There, she was soon admitted to hospital for exhaustion. She left hospital after a week and returned to her mother’s home. On the weekend, she visited her sister’s home, where she killed herself.

Within days this story captured national attention and was widely covered by major media outlets in the United States and beyond. This was no surprise. The narrative adopted in virtually every story was: selfless doctor works doggedly to save the lives of COVID-19 patients – including her own colleagues – contracts the disease herself and then dies by suicide as a result of the physical and mental toll her heroic efforts had upon her.

On April 27, the New York Times ran an accurate and restrained piece by four reporters – Ali Watkins, Michael Rothfeld, William K. Rashbaum and Brian M. Rosenthal. The story was highly detailed but did not include the method of suicide, only describing her as having died of “self-inflicted wounds.” It also provided context, describing Dr. Breen’s work life, her social world, hobbies and other pursuits. But in the stories that followed, serious problems emerged. First, almost every subsequent story employed the word “hero” to describe Dr. Breen and employed a more glib narrative that leaned toward a romanticization of her death as a “fallen soldier” in the war on the pandemic. This narrative line was strongly reinforced by quotes included in many stories from Dr. Breen’s father, Philip, who characterized his daughter’s suicide in military-service terms. "She was in the trenches," he said. "She was a hero.” Mr. Breen went further, invoking military language to describe his daughter’s death: “She went down in the trenches and was killed by the enemy on the front line.”

Dr. Breen’s dedication and service during COVID-19 was accurately described as “heroic” in the stories, readers could get the impression that her death was also being viewed in that light. As well, because her death was so closely linked to her sacrifices during the pandemic, the stories contravened several of Mindset’s “Suicide Dos and Don’ts” including, “Don’t accept single-reason explanations uncritically. The reasons why people kill themselves are usually complex with multiple factors interacting.” In several stories, prominence was given to quotes that pointed to one cause for her suicide, for example, “She tried to do her job, and it killed her.” This reason was bolstered by statements from family members that Dr. Breen “did not have a history of mental illness.” This narrative could leave readers with the impression that a reasonable solution to stress and hardship is suicide.

Instead, the Mindset recommendations suggest presenting suicide as multi-factorial and “as mainly arising from treatable mental illness, thus preventable.”

Though it is journalistically acceptable, perhaps even desirable, to have powerful quotes from family members in a story on suicide, it is important to offer context to any claims made by non-experts. In some stories, this was accomplished by the inclusion of a balancing quote from a medical person that offered a more nuanced view: “A death presents us with many questions that we may not be able to answer,” said one doctor interviewed.

Virtually all the stories were successful in linking Dr. Breen’s death to broader social issues, such as work stress and emotional strain, particularly for front-line workers in the pandemic. They also, universally, offered mental health and suicide prevention resource information at the end of the stories.

Suicide Case #3

Campus suicides: University of Toronto and Concordia University

On Sunday, March 17 2019 around 8 p.m., police responded to a death at the Bahen Centre of Information and Technology, University of Toronto. Initial reports were that a student “fell to his death” from the roof of the building.

The basic facts of the incident were relatively simple, but complex issues around coverage emerged almost immediately. Like almost all universities where a student suicide takes place, the U of T dealt with it as a private matter, not for public consumption. The administration issued a brief statement on Twitter just after midnight on March 18: “Members of our community may have been affected by the recent incident at the Bahen Centre. At this time, we wish to respect the privacy of the individual involved and acknowledge the profound effect on family, friends and colleagues.”

Almost immediately, details of the death – including the name of the student and how he died – circulated on social media, including Twitter and Reddit.

With little being provided by the police – no crime was involved – and nothing coming from the university or the family, the media had little to go on and this suicide, like many that take place in private homes across Canada, would normally have remained largely unreported.

But by Monday, concerned students organized a public protest regarding three suicides at the U of T in 2019, none of which had been openly acknowledged by the university. The students' actions and concerns were widely covered in campus media and then, somewhat later, in mainstream news outlets. The protests demanded coverage and forced journalists to confront several difficult questions: Was the death newsworthy? How far should they go out of respect for the privacy and grief of the family? Did the death raise issues of policy of interest to the public? In this case, because the suicide had occurred in a public place and a highly-visible student protest ensued, the event warranted coverage. Under pressure, the university eventually responded providing more information to a campus media outlet. “On Sunday night, a student fell to his death at the Bahen Centre. The family has asked us to keep information about their child private. We are honouring their wishes, and providing whatever assistance we can to them at this heartbreaking time,” said Sandy Welsh, Vice-Provost, Students. The next day, on March 20, on a popular Toronto morning radio show, [CBC MetroMorning] U of T president, Meric Gertler repeated the phrase “fell to his death” and told listeners that the school had not used the word suicide, “out of respect for the family.”

Most stories about the incident followed Mindset recommendations in not sensationalizing the death, in not providing specifics of method or unnecessary details and in protecting the privacy of the deceased. At the same time, the stories succeeded in exposing student concerns about rising mental health issues on campus; the lack of available and timely counselling on campus; and the university’s consistent reluctance to publicly acknowledge the ongoing issue of campus suicides, treating each death, as one columnist put it, “as an isolated incident” rather than as part of an ongoing mental health crisis. The stories also covered the student demands for grief counselling and public mourning events. Virtually every story that followed the Toronto suicide adhered to Mindset recommendations and provided extensive lists of phone numbers and website addresses for suicide prevention and mental health resources.

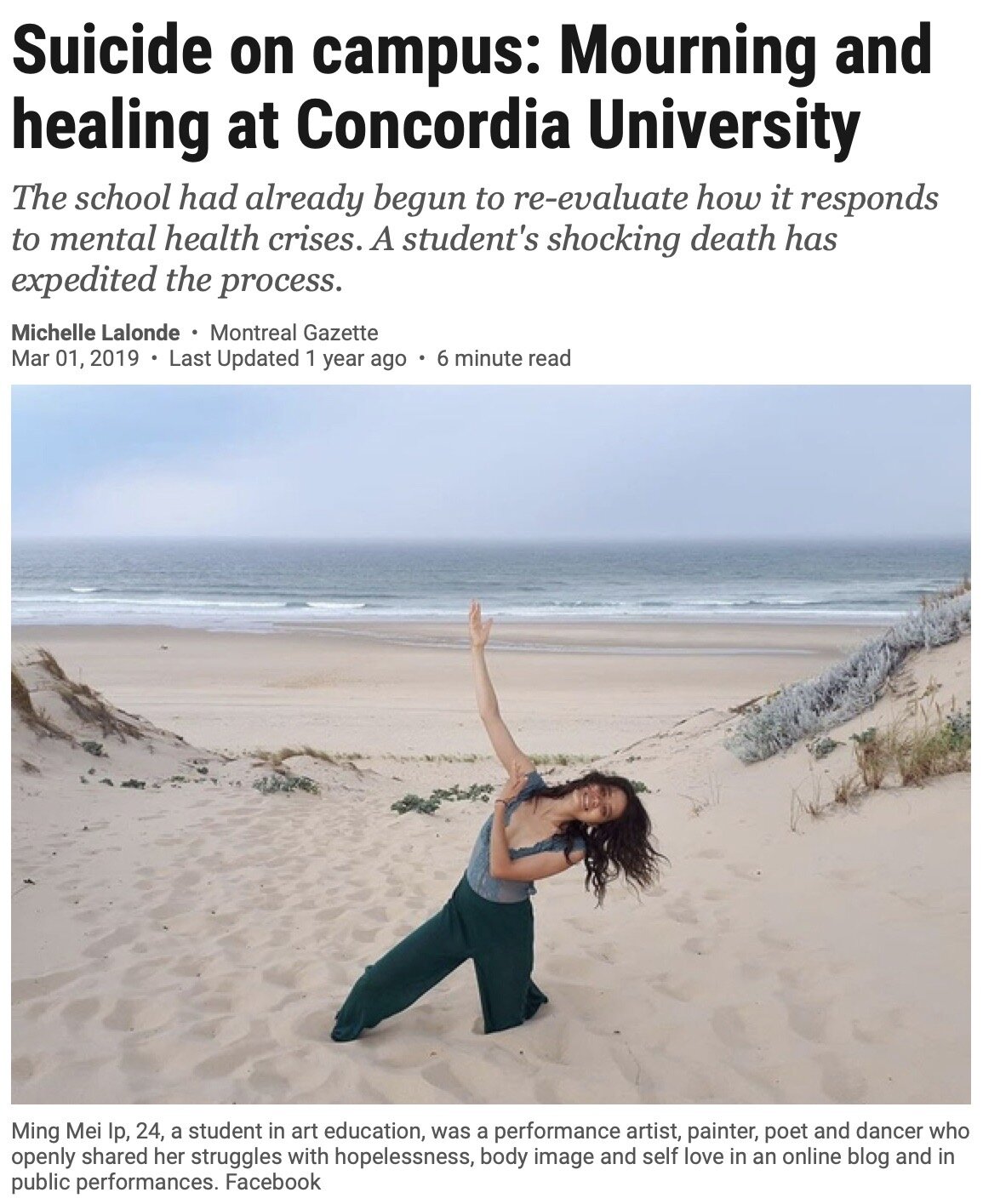

In Montreal, the same basic facts played out with somewhat different outcomes in information flow and subsequent coverage. There, on Friday, February 15, Concordia University student, Ming Mei Ip, 24, was found dead in a studio in the Visual Arts Building. Again, the same thorny issues were in play: balancing the news value of the death with respect for the grieving family; the reality of the news spreading on social media; and the need to address the stigma of student suicide as a public interest issue. In the Montreal case, reporters had access to more information in a more timely fashion. Within hours of Ms. Ip’s death, the university sent an email to all Fine Art students acknowledging her suicide and providing mental health and counselling information. By Monday, the university, with the cooperation of Ip’s parents, had taken a series of extraordinary steps including printing posters announcing her death, bringing in counsellors, arranged grief workshops and scheduled a healing ceremony in the building in which the death had occurred.

Two weeks after the death, On March 1, a major media outlet [The Montreal Gazette] ran a long, detailed story on the suicide, naming Ms. Ip and detailing the reaction of the university and the student community. The story contextualized the suicide and provided background about the issue in a balanced, thoughtful manner. It stated, “The classic response to suicide on campus has been to hush it up and release as little information as possible in the hope that students and faculty can quickly move on. However, this approach — defended as respectful of the privacy of the deceased and family members — can add to a sense of shame and secrecy around suicide that mental health professionals say is counterproductive.

At Concordia, as soon as Ip’s family gave the administration permission to speak publicly about the suicide, officials worked to get the word out to students and faculty, allowing many of those who knew Ip to attend the visitation organized by her mother on Feb. 19.”

The story also provided background information on student mental health and suicide rates as well as a list of phone numbers and resources for mental health and suicide prevention.

In the Montreal case, the university and the media responsibly adhered to the Mindset recommendations while providing nuanced coverage. As André Picard wrote in a Globe and Mail column addressing the two suicides, “In the short term, we have to act to prevent young people from hanging themselves and throwing themselves from university towers. We won’t do that by pretending it’s not happening, or by averting our gaze. The silence about suicide on campuses is sickening – literally and figuratively.”

SEE ALSO: Suicide Contagion Studies